This instalment of my infrequent art/film communiqués looks at Atavistic Cinema, a cinema which seems to want to return to the place of cinematic origination, taking a path that might lead to the regressive terminus of film and, perhaps, to the place for its creative renewal. I also muse upon cinematic boredom, a terrain that any enthusiast for artists’ films is no doubt familiar with. In other news, writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent is returning to the landscape of his past, revisiting his childhood home town of St Leonards-on-Sea to curate an exhibition which pairs work by some of this area’s artists with work by their international doubles. Finally, I’ve made a couple of recent films of mine available to watch online, one of which seems to contain a bizarre presence, of unknown origin. Approach this otherness below.

Michelangelo Antonioni, Red Desert, 1964

Origination

Cinema lives through motion. To work against it, or still its passage, is to subvert the medium itself. Filmmakers and artists have used the still image, or something approaching it, to return us the pre-cinematic stillness that resides in the stationary photograph. In the cinema of Michelangelo Antonioni, characters sometimes seem to be about to freeze, suggesting emergent statues rather than protagonists, figures from which the camera disinterestedly drifts. Looming stasis and a growing indifference to plot are key symptoms of the regression toward cinematic atavism. Going further, Chris Marker’s 1962 classic La Jetée, is composed of still images throughout, with one very brief exception when, as if arising from a frozen dream, the film magically flickers into life. Still and moving images fuse in Hiroshi Sugimoto’s work, which I had the option to view at length at last year’s retrospective at Hayward Gallery. The photographs in his Theatres series (long exposures taken within the cinema, condensing an entire film into a single image) seem to distill cinema, whilst suggesting its ultimate erasure. Recent works from this series show dilapidated auditorium interiors lit by what might well be the terminal illumination of film. Despite this, I like to see his images as documenting sites of technological visitation, mystical moments of regenesis amid the ruins of an obsolete world.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Palace Theater, Gary, 2015

Chris Marker, La Jetée, 1962

Reptile Time

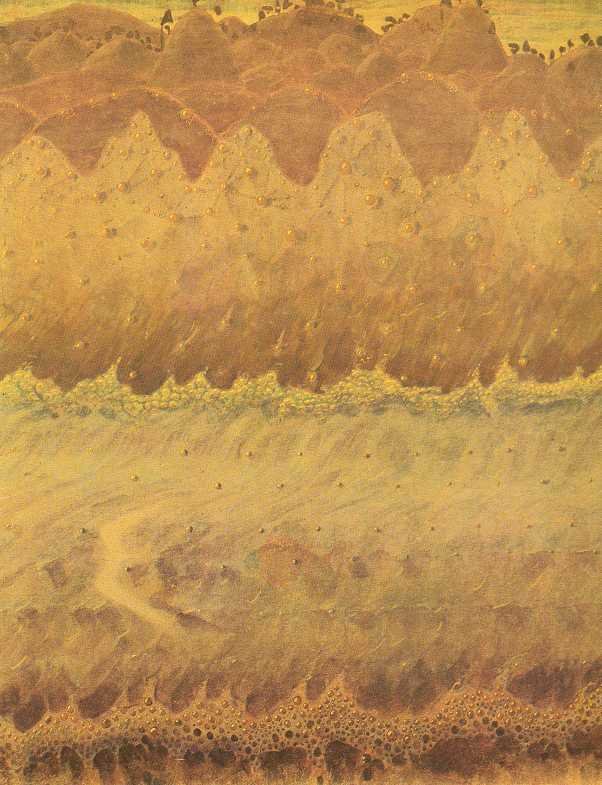

In my own work, I approach cinematic devolution through engaging with atavistic imagery, dredged from the somnolent storehouses of ancestral memory. I often make use of the still image, fusing it with an aesthetic of deeply subjective expressionism. To me, there is a sense of tension in the work arising from the odd combination of the excessively Romantic imagery and the somewhat detached presence of the lingering, static camera, which often seems to situate the spectator outside the fantastic world they are invited to peer in at - the screen as a locus for visions as well as a defensive barrier. My films usually present a fixed viewpoint onto a largely unchanging world where, within the atavistic stillness, if you have the patience to attend to it, another order of movement abides. Time in these films unravels at different rhythms, suggestive, perhaps, of the patient biorhythms of reptiles or the deep timescales of planetary undulations.

The Green Mind, 2013

My two most recent films The Nursery of Worlds and A Spell in Fairyland (both 2022) are further voyages into this expansive terrain. The Nursery of Worlds makes use of low-resolution footage gathered a decade before, with the film emerging as if having been dredged from obsolete slumber. This rediscovered material was reworked into something approximating a seething primordial ocean, where, over the course of the film, hallucinatory forms gradually arise and dissipate. During a single unbroken sequence, the camera languidly drifts over this fertile amorphous space, as if showing a view through some cosmic submersible’s porthole or, perhaps instead, a scene through a microscope, detailing the subcellular life contained within an alien biological sample. Towards the end of the editing of A Spell in Fairyland I noticed something strange in one of the sequences in the film, the suggestion of an uncanny presence that seems to exist underneath the dark, slowly flowing water. After spotting this aqueous presence I had the spooky sense that somebody or something was trapped inside the film, as if held spellbound. This sense of entrapment fits with the themes of the film though, as fairyland is often thought to be an underworld where, once lured to, you might never return from. In some way it is as if the experience of watching these films is reflective of the experience of me making them. In gathering the footage for these projects I would spend countless hours roaming outdoors, without any real plan, sitting by streams, seemingly half awake, waiting for the passage of the sun to partially illuminate a mysterious grotto. During these outings a different sense of time takes hold, a time that now permeates the works themselves.

The Nursery of Worlds and A Spell in Fairyland are now available to watch here and here. If you do decide to encounter these artworks, I’d advise doing so in the dark, when you have a bit of time to spare.

The Nursery of Worlds, 2022

A Spell in Fairyland, 2022

Boredom

Traditional cinema diverts us from boredom, unveiling a torrent of distracting visions that can transport us out of ourselves, projecting us vicariously into another world. Arthouse film and experimental cinema often takes an opposite approach, as if suspicious of the heady intoxication of cinematic spectacle. To me, sometimes this disavowal can seem like the actions of some niche cinematic sect, dedicated to the denial and dissolution of fanciful visions. Perhaps, for this imagined hardcore group, only the stark glare of the projector’s beam would represent true cinematic illumination - the screen’s unmitigated whiteness shorn of the deluding miasma of the filmic phantasmagoria. As somebody who came to life watching weird cult movies on late night television, relishing their lurid colours, their sense of abandon, their transgressive narratives and their potential for imaginative escape, I remain somewhat ambivalent about theoretical critiques of film’s pageant of illusions.

In an attempt to counter the spellbinding hegemony of cinematic immersion, numerous film-makers and artists have opted to occupy a different space in relation to the mechanics of the moving image. One approach to wresting some control over this industrial mirage is to slow things down, allowing the viewer to be more aware of themselves as active participants in the process of a film’s unfolding.

My first encounter with cinematic boredom came at a 35mm screening of Jean Eustache’s 219-minute-long masterpiece La Maman et la Putain (1973). I’d gone in cold, without noticing the digressive runtime. Somewhere amid this ocean of celluloid a protagonist puts on a record and then just listens to it, seemingly aimlessly, whilst the camera keeps rolling. I kept expecting the shot to cut away, but it refused to, the film just kept going. As I watched this dilating sequence endlessly unfold a strange tension seemed to build, a tension arising from the seeming abandonment of hitherto familiar editing protocols, inaugurating a sense of my floating free, becoming unmoored, of entering into some other time-space. As the film kept unspooling I noticed that, as if some sort of threshold had been crossed, I became increasingly drawn into this scene of drifting cinematic life and found myself inwardly urging the shot to continue, perhaps indefinitely… Behind these extended sequences, where the camera is seemingly left to run freely, one begins to sense the gaze of the observing machine, the active presence of the medium itself, and of us out there in the dark, engaging with it as spectators.

Jean Eustache, La Maman et la Putain, 1973

Primal Cinema

Tony Conrad’s 1966 film The Flicker, which I encountered recently, screened at the East Sussex Psychedelic Film Club, returns us to cinematic ground zero via the most extreme form of rapid fire editing, triggering an aggressive onslaught of monochromatic psychedelia. Conrad’s 30-minute film is one of considerable formal simplicity. Aside from the credits sequence, the entire film consists of two images - an image of whiteness (for this Conrad filmed a blank sheet of white paper) and an image of darkness (which utilises footage shot whilst the camera’s lens cap was still in place). Conrad switches between these two extremes with excessive rapidity, causing the film to inaugurate a change of consciousness in the viewer. Conrad’s film continually modulates this flicker rate, bringing the audience in and out of various kinds of altered states. Despite the paucity of imagery I found, during the experience of watching the film, that odd images half-formed in front of my eyes, while the transfigured screen seemed to warp and bulge out toward me.

I’ve included a link to a version of the film I found online below, which I include here with the following proviso: Tony Conrad himself recommended that a doctor be present at each screening of the film, to assist with any issues arising from the potentially seizure-inducing flickering effects. If any readers are susceptible to intensely flickering images I would, of course, advise not pressing play. For those willing and able to encounter this barrage I’d recommend doing so in the dark, at the largest scale possible.

Encounter The Flicker here.

Tony Conrad, The Flicker, 1966

St Leonards International

Writer and curator Paul Carey-Kent is staging an exhibition of work by a number of artists based in and around the St Leonards, East Sussex area. Paul has taken the further step of pairing these participants with a parallel group of international artists drawn from the wider world. I’ve been matched with artist Tereza Bušková, who hails originally from Prague. Tereza will be showing her film Little Queens, which will be paired with my film The Garden.

According to Tereza, Little Queens “takes inspiration from the ancient Moravian festival of Královnicky, which is best translated into English as The Little Queens. On the cusp of spring and summer, rural communities used to celebrate their daughters in order to strengthen their own connection with nature and assure a bountiful harvest. Some elements of this ritual have been lost to time, but through a collaborative process the participating communities revisited and restored The Little Queens for a 21st Century audience. Surrounded by their attendants clad in festive raiments, the King and the Queen walked under an ornate canopy and gave blessings to all good people of West Bromwich. The ultimate creation was a richer, more cohesive community, one that can weather the relentless waves of anti-immigration sentiment, misogyny and xenophobia”.

Tereza Bušková, Little Queens, 2022

Made in 2019, my film The Garden is composed of only two extended shots, both showing variations on a manufactured garden of outsized plants and rock formations, which are subject to a prismatic incursion of shimmering lights. The film’s title seems simply descriptive, and it does describe the film - the garden being a bordered, organised outdoors, set apart from the riotous, inhuman sprawl of nature - but it also brings to mind the Biblical garden, the prelapsarian space where the serpent lurked. Perhaps the first of the film’s two gardens might represent some sort of elevated spiritual realm whereas the succeeding space, emerging from the river of serpentine lights, suggests a more sensual realm, perhaps even a fallen world. At the time, I was making The Garden, I considered it representative off what I liked to call Psychedelic Romanticism, with the film being psychedelically Romantic not only in its streams of colours, but also in its emphasising of flowers and plants and in the open-ended, ambient time-space that it occupies.

St Leonards Meets The World features:

Geraldine Swayne + Miho Sato (Japan)

Hermione Allsopp + Blue Curry (Bahamas)

Colin Booth + Koushna Navabi (Iran)

Toby Tatum + Tereza Bušková (Czech Republic)

Joe Packer + Robyn Litchfield (New Zealand)

Alice Walter + Kristian Evju (Norway)

The exhibition runs from the 17th to the 27th of May.

Electro Studios Project Space, Electro Studios, Seaside Road, St Leonards-on-Sea, TN38 0AL, U.K.

The Garden, 2019